Artists have long used plants as subjects of their artwork. Botanists use botanical art portraits of these plant subjects as identification tools.

Marianne North traveled around the globe painting plants, defying Victorian conventions. She documented everything from California redwoods to Bornean pitcher plants.

Botanical art

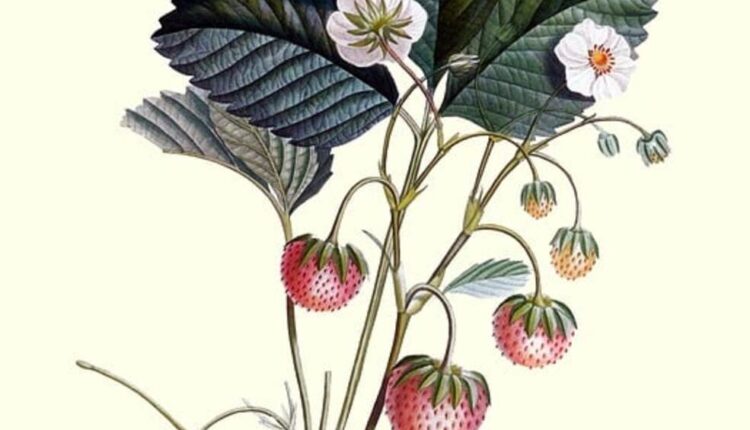

Botanical art is a specialized branch of fine arts that focuses on painting and drawing plants. Artists utilize botanical art to illustrate different species while aiding scientists. Botanical artists must capture each plant’s character, form, and detail while remaining scientifically accurate – this can be accomplished using various mediums such as water-based paints, colored pencils, gouache paints, oils or inks on paper/vellum/mylar, and silverpoint on archival support.

Botanical illustration may also be done in still-life settings with objects like vases and other accessories; this differs from floral art, which may be more impressionistic and focus on pleasing images instead of botanical accuracy. Historically, botanical illustrations were employed to record and identify plant species for medicinal and other uses; as printing technology improved and botanical taxonomy expanded, demand for botanical illustrations decreased substantially.

Leonhart Fuchs, a German physician and botanist, created the first botanical illustrations in 15th-century medical herbals by hand-coloring woodcut engravings using hand tools he created from woodblock engravings in medical herbals. These woodcut engravings made a significant step forward from previous works by highlighting characteristics distinguishing one plant species from another.

In the 18th century, botanical artists like Sydney Parkinson and Ferdinand Bauer documented new plant species during scientific expeditions around the globe. Their botanical field drawings contributed to our understanding of global plant diversity – today known as Banks Florilegium.

Botanical art provides an essential record of Earth’s ever-shifting ecosystems. It is a beloved way of honoring native plants and flowers, teaching children about our environment, and showing its value to society. Botanical illustrators frequently work with scientists, environmentalists, horticulturists, galleries, etc., to produce accurate depictions of plant life.

Future botanical artists will continue to contribute significantly to our understanding of nature and biodiversity protection by documenting morphology, coloration, and other distinguishing characteristics of individual plants. Furthermore, their contributions will aid researchers studying climate change’s effect on fragile ecosystems.

Botanical illustration

Botanical illustration bridges the gap between art and science, with artists striving to accurately represent plant and flower species visually while producing pleasing images. The balance between these elements may vary according to each work, as botanical drawings and paintings serve multiple functions, including supplementing herbaria collections and informing non-expert audiences about the lifecycle patterns of various plants.

Botanical illustration dates back to antiquity. Herbaria were published to help readers identify medicinal plants and their properties; illustrations called Florae or florilegium often came with descriptions and notes regarding how best to use them. Many well-known illustrators, like Heeyoung Kim from Victorian Britain, have made careers out of creating detailed watercolor depictions of plants and flowers; their artwork can take up to 40 hours per piece and must be meticulously accurate.

Botanical drawing is an intricate science, and botanical artists must collaborate closely with scientists to achieve accurate depictions. An experienced botanical artist should be able to distinguish between mature and immature flowers or fruits, drawing them at any stage in their life cycle; additionally, they may illustrate cross-sections through seeds or fruits as well as details regarding the habitat and growth habits of the plant they depict.

Botanical illustrators play an invaluable part in research. Relying on them for accurate records that help with identification is priceless while acting as a proofreader for scientific descriptions is equally crucial. Although digital photography has become more widespread, it cannot convey all the intricacies needed for accurate portrayals or reconstruct pressed plant specimens into lifelike specimens like botanical illustrators do.

Botanical illustration remains relevant today as our natural environment becomes ever more threatened by rapid environmental change. Botanical illustrations offer a cost-effective means of documenting plant species while working in traditional media ensures the long-term preservation of sketches, paintings, and etchings.

Early botanical illustrators

Botanical artists have long depicted plants for decorative and medicinal use, from ancient Egypt’s depictions on temple walls to Greek ceramic decorations adorned with plant illustrations. At first, botanical illustrations were hand-copied from herbal books; during Europe’s Renaissance Renaissance, artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Durer contributed their remarkable skills in making plant illustrations more useful, accurate, and beautiful.

Woodblock printing made botanical illustrations simpler to produce and share during the 1400s, as botanical artists could draw images of specific plants directly onto woodblocks that could then be inked and printed onto paper for distribution. With the development of movable type printing technology, this increased public access to botanical information.

Botanical illustration evolved, becoming more detailed and colorful as artists specialized in depicting certain species; some species, like the flower fuchsia, even bear names of notable artists whose artwork had inspired it.

By the Victorian era, botanical art had become more ornamental and less naturalistic, yet remained an indispensable tool for disseminating botanical knowledge. At that time, many publications hired dedicated botanical artists who would produce meticulous drawings of specific plants for publication purposes.

With our current environmental crisis and widespread species loss, botanical illustration remains indispensable. While digital photography may make this more accessible than before, its incapability to accurately represent individual plants requires meticulous drawings by skilled botanical artists with knowledge of plant anatomy – something digital photography cannot capture.

Botanical artists today continue to draw, paint, and illustrate using various media. Most commonly use pen and ink, but color can also be employed provided that an artist accurately captures critical structural features of plants and depicts their ecosystems.

Marianne Northiana

Marianne North was an accomplished botanical artist, explorer, and one of the world’s most well-traveled women of her time. She painted nearly 900 paintings showcasing 727 plant species from six continents across six decades, living alone while defying conventions that dictated women marry and follow their husbands abroad for marriage purposes.

Marianne was born in Hastings and died in Alderley. Frederick was a wealthy landowner and politician who encouraged Marianne not to remarry after moving abroad, to travel freely and paint what she saw. Thus, she became a botanical explorer, traveling to far-flung locations searching for plants that captured her imagination.

She distinguished herself from other botanical artists of her day by painting her subjects in their natural settings rather than as isolated specimens, enabling her to capture all their beauty and complexity and delighting explorers such as Francis Galton and Charles Darwin.

Imagine her in the thickets of the jungle, dressed as you might expect a Victorian woman to wear, with an easel in hand, painting with abandon, oblivious to anything but botanical subjects and her art.

Her painting style was meticulous, using only limited palettes to limit how many materials she needed to carry with her. Blue, green, or orange tones may have been chosen to soften intense hues – giving her paintings an intensity that digital printing cannot replicate.

In her later years, her health deteriorated, but she never stopped painting. Even after losing her eyesight completely, she continued to see the world through unique lenses that few could understand.

Marianne reached old age as an elderly widow, still focused on exploring nature and its marvels. Her autobiography chronicles her travels to far-flung destinations such as the Pacific Islands, Japan, China, and Borneo without fearing hardship; instead, she finds comfort wherever possible with easels and brushes in hand.